“It was a place where we came together as a community, not just where we came on Sundays, but where we could get together to solve the problems of the community. It was a place we could call ours,” she says.

The announcement of the church’s closing in early 2004 came at a moment when Jamaica Plain was undergoing a wave of gentrification. The neighborhood has long been a destination for new immigrants, first German and Irish in the early 20th century, and more recently Dominicans, Cubans, and others from Latin America. Though it always had a few wealthier sections, much of Jamaica Plain was and still is working-class. But in the past decade, many affluent young families have discovered the area’s leafy streets. Their growing numbers have made J.P., as the neighborhood is affectionately known, one of Boston’s hottest real-estate markets.

Community activists had worked tirelessly for nearly three decades to revitalize the area, but their success was getting out of hand. Prices for housing and retail space had skyrocketed, making it increasingly difficult for nonprofit developers to build affordable housing and for small retailers to continue to cater to low-income residents. The Archdiocese of Boston was about to place a huge piece of real estate on the market, and private developers were salivating at the prospect of turning it into market-rate condos. The fate of the church and its surroundings promised to play a pivotal role in the community’s future.

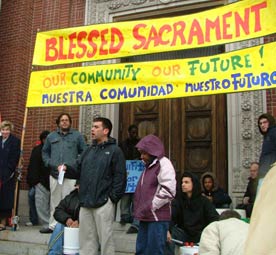

Affordable-housing activists, many of them former church parishioners like Gutierrez, got organized. They helped the Jamaica Plain Neighborhood Development Corporation (JPNDC), a nonprofit group founded in 1977 that had strong support in the neighborhood, to organize residents in favor of its proposal to redevelop the Blessed Sacrament church as affordable housing. In the fall of 2005, the church accepted JPNDC’s purchase price. But then came an unexpected wave of opposition from middle-class homeowners who lived nearby. They claimed there was too much affordable rental housing in the neighborhood already. So residents had to rally again, to make sure this opposition did not make their initial victory hollow.

Whatever sense of denial Gutierrez might have felt about the church’s impending closure ended when she stepped inside its doors a few months later and saw it stripped of its stained glass and other wonders.

“We knew that we had no power and nothing could stop this,” she says. “The memories were gone.” But in its new incarnation as housing, she adds, the building will still have meaning to her. “The community still has control.”

The Activist Church

The massive dome of Blessed Sacrament, completed in 1917, towers over Centre Street and the two- and three-story homes of what has historically been a working-class neighborhood. The church served a largely German immigrant population that labored in the nearby breweries and a shoe factory. It was built as a boastful answer to another huge cathedral closer to downtown, constructed some years earlier to serve mostly Irish-Americans.

Jamaica Plain went through dramatic changes in recent decades, beginning in the turbulent 1960s. White residents moved to the suburbs in large numbers, and people of color often took their place. To help commuters travel in and out of the city faster, city and state leaders planned an interstate highway through the neighborhood that required tearing down hundreds of homes. The effect of these changes was that property values plummeted and the community became vulnerable to the ills familiar to many urban areas, from blockbusting to street gangs.

Given its power in Boston, a heavily Catholic city, the archdiocese had the ability to play a significant role in local affairs, if it chose to. Most often, however, whether an individual parish moved to influence its surrounding neighborhood depended on its own leaders, not that of the mother church in downtown Boston. During the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Blessed Sacrament was led by a priest, Richard Donahue, and parish staff who cared a great deal about the turmoil engulfing Jamaica Plain.

“They had a good understanding of all three [black, Latino, and white] communities that were there then,” recalls Sister Virginia Mulhern, who worked at Blessed Sacrament until a few years ago as a pastoral minister, helping the church with education and outreach to the community. “We tried to make one roof for all the different cultures.”

Beyond making the church hospitable to newcomers, the leadership addressed the community’s problems head-on. In response to the proposed interstate highway, Donahue and Francis Clougherty, another pastor, started Catholic Community Concerned About the Corridor. The group held a workshop at a nearby community college to educate residents about what might happen whether or not the highway was built. A backlash against highway building led the state to abandon the Jamaica Plain road in 1974, but by that time many homes had been demolished and a swath of empty land ran through the neighborhood.

Comments