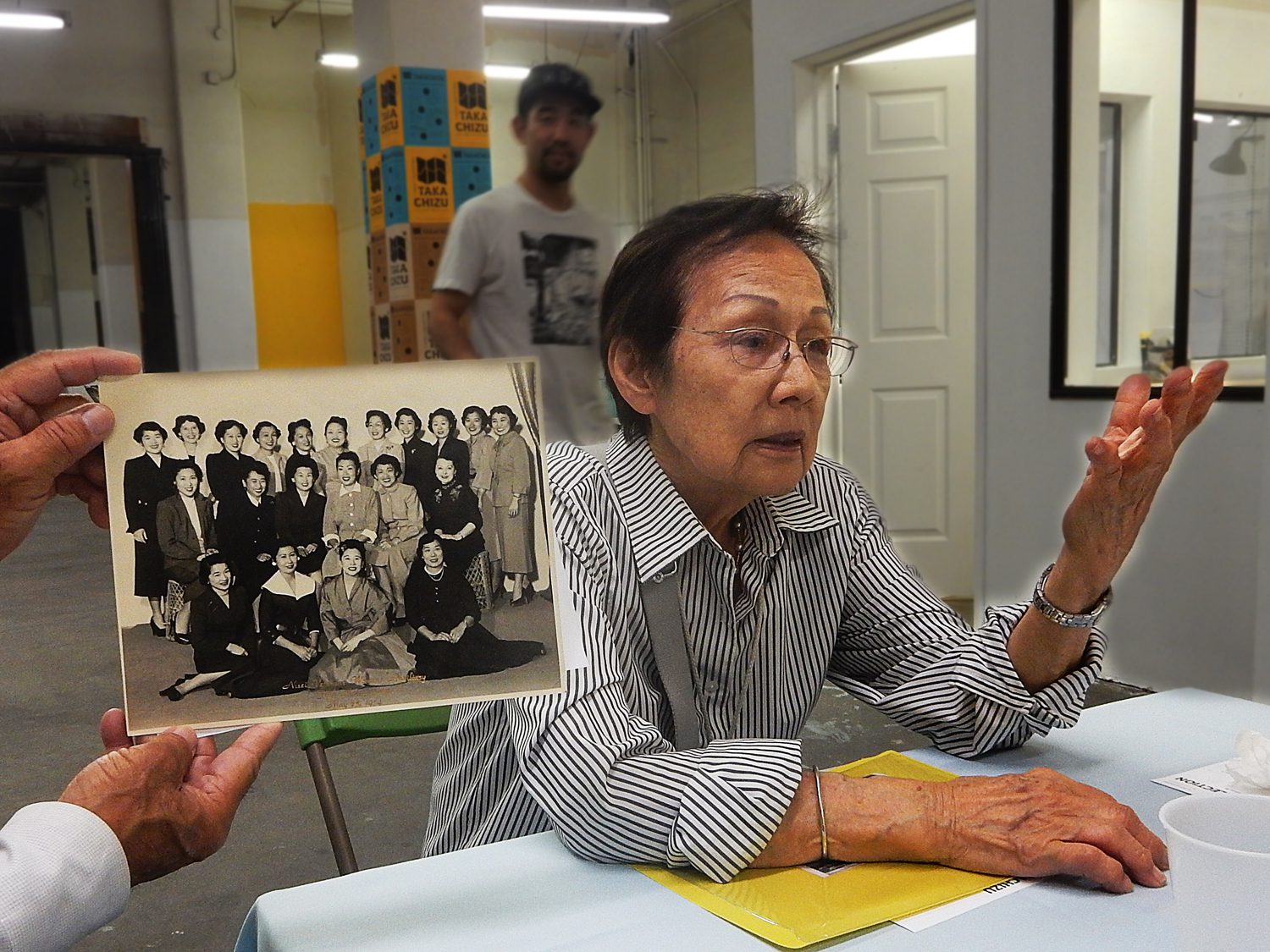

Yae Aihara talks about a 1954 photo of the Nisei Veterans Women’s Auxiliary, the women’s organization in Little Tokyo. Photo courtesy of Mike Murase

Grace Chikui, 53, relies on walls, the edges of grassy areas, and the feel of the asphalt under her feet when she needs to go somewhere. In the short documentary film, Walking with Grace, Chikui explains how she lost her sight to glaucoma when she was a child. But the neighborhood in Los Angeles known as Little Tokyo is familiar to her and she feels comfortable walking around. She can tell whether she’s in an open area or passing by a building by how the air feels. “When the sun is shining, I could see a little bit, like maybe the building’s shadow. I don’t get lost,” Chikui says in voiceover. In the film, she turns a corner, her light orange dress and sunhat a bright spot against a concrete wall, her cane tapping side to side before her like a metronome.

But those streets might not be familiar for long. “I hear about new changes from other people or I hear construction going on,” says Chikui. “[In] the early days, people were all Japanese, but now I hear all different languages like Spanish or Chinese or Korean. The old-timers are going away.” Chikui doesn’t consider herself an old-timer—at least not yet. But the prospect of disappearing doesn’t seem far off. Kristin Fukushima at Sustainable Little Tokyo puts it more bluntly: “We feel like we’re losing a little piece of Little Tokyo’s soul,” she says. The organization supports green initiatives, small business development, and cultural and artistic programming that recognizes and preserves the unique heritage of the area. “Things change and we want to evolve and be dynamic, but we don’t want to lose the core character of who we are, which can be somewhat undefinable.”

What is the core character of Little Tokyo? How can defining that character help to preserve it and ensure that residents like Chikui continue to find their way?

Be Experimental

In an epic poem about “place and people and art in four parts,” traci kato-kiriyama, a multi-disciplinary artist and community organizer with deep roots in the Little Tokyo community, pays tribute to artists of Japanese descent who were imprisoned in American concentration camps during World War II. Their art was “created to survive the insanity of injustice, to thrive past the stench of forced silence,” writes kato-kiriyama, who is also a co-founder of Tuesday Night Project, which presents the longest running Asian-American open mic series in the country. Art was a lifeline not just for the individual artists, but for an entire community of people forcibly removed from their homes and neighborhoods and targeted for belonging to an ethnicity that was suddenly labeled as an “enemy.” Making art was a way to confront and resist the discrimination Japanese-Americans endured at the hands of their own government, a reassurance of humanity. “Art—the lightning between the synapses, the conversation between hearts, the amplification of our history, why any good argument begins with [an] anecdote—this is the necessity of art, to help us draw from a different well when the ones we’ve always used have run dry,” kato-kiriyama writes.

Her reflection on the role of art comes at a critical time for the neighborhood. Throughout its 130-year history, Little Tokyo has pushed back against discrimination, the impact of wartime internment, and economic devastation. Today, it is one of only three Japantowns left in the United States. (At one time, California had more than 40 Japantowns.) The nine square blocks that constitute Little Tokyo are home to over 5,000 residents, many of them seniors, and a wealth of cultural institutions, including museums, Japanese gardens, tea houses, galleries, and Buddhist temples. It is a prime destination for out-of-town visitors, touted by Time Out Los Angeles as the “ultimate destination for some of the city’s best Japanese restaurants and authentic shops.” And, with the expansion of the public transit system, it’s close to downtown Los Angeles and a hot housing market fueled by private investment. Little Tokyo stands directly in the path of economic forces that threaten the identity of the historic neighborhood.

“There is no question in our minds that we are at a crossroads as rapid gentrification of downtown Los Angeles is quickly changing our neighborhood,” said Dean Matsubayashi, the executive director of Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC), after the organization was selected to receive a Community Development Investments (CDI) grant from ArtPlace America in 2015. “We basically have two choices in front of us. We can either shape our future or be shaped by the many pressures, policies, and plans that are being imposed upon us right now.” By leveraging the arts, a resource of which there is no shortage in Little Tokyo, LTSC is shaping a vision for the future in which local businesses are sustained, the rich heritage of the community is celebrated, and environmental sustainability and social equity remain priorities.

Learning to Talk the Talk

Simple chores taken for granted in familiar surroundings become huge challenges in a new country. Mailing a letter, paying a utility bill, filling out government forms, and getting around town—daily tasks that are tedious even in one’s native tongue—are suddenly daunting. Add to that cultural isolation and unpredictable flashes of outright bigotry, and the experience of immigrating can be overwhelming.

In 1979, LTSC was established to help ease the transition for Issei—Japanese-speaking, first-generation immigrants—for whom limited English proficiency made day-to-day life difficult. In the four decades since, LTSC has expanded to provide a wide range of social services to a diverse community of Asians and Pacific Islanders in Los Angeles County, including programming for seniors, youth mentorship, child care, advocacy for the cultural and historic preservation of Little Tokyo, and, crucially, the development of affordable housing and community facilities.

Through all of these initiatives, the one thing LTSC hasn’t done until now is bring the arts on board as part of an integrated development strategy. It’s not that culture hasn’t been a part of LTSC’s work in the past. “We’ve never not partnered with arts organizations or employed artists or deployed creative strategies, but I wouldn’t say it’s been a deliberate strategy,” explains Rémy De La Peza, LTSC’s director of planning and policy counsel. She recalls Little Tokyo’s old Union Church building, which was established in 1923 and left vacant after it was damaged during an earthquake in the 1970s. In the late 1990s, LTSC transformed the property into the Union Center for the Arts, home to three arts organizations, including an Asian-American theater ensemble called East West Players, and Visual Communications, an Asian Pacific media arts center. This sort of intervention, while supporting the survival of three bodies dedicated to the arts, was, as De La Peza puts it, a “knee-jerk reaction.” The property needed development, the organizations needed space, and LTSC was positioned to make sure those needs were met.

In contrast, the ArtPlace grant is a chance for LTSC to figure out how to take a more intentional approach toward engagement with the arts. “The major shift for us now is how do we, on the front end, really start trying to find those opportunities and seek them out, but in a way that is still consistent with being a community development organization and not trying to become an arts organization,” De La Peza says.

So far, laying the groundwork for this shift has been a painstaking venture. “I don’t think anybody quite understood, when we were awarded the grant, how thoughtful of a process it needs to be,” De La Peza says. The easier route would have been adding a new department to the organization and hiring staff who would be charged with working with artists and implementing arts projects. But the CDI program is about the integration of arts and culture throughout the organization—a far more complex process.

“Integration of arts and creative strategies into an existing community development organization requires a real look at how we’re doing community development work now and how we communicate why we’re doing that work—both internally and externally,” De La Peza explains. “It’s re-creating our internal organizational structure and helping us realize where we haven’t been totally clear before. We need to get that clarity about our existing work first before we can figure out how arts and culture fits in.”

Embedding the arts in all the diverse facets of the organization, such as youth mentorship, health care, and senior living, rather than just community planning, is a challenge. “There are a lot of starts and stops and sometimes it feels like we’re building the plane while we’re flying it,” De La Peza says. “But I think in the end, going through this process is also helping us solidify our community development work as a whole.”

Maya Santos hopes to help bring a little more clarity to the process. An artist with a background in architecture and the head of multimedia studio FORM Follows Function—which produced Walking with Grace—Santos joined LTSC in March 2016 as a place-based programmer and works alongside De La Peza and Dominique Miller, the organization’s planning administrator. “Coming in, I feel like a creative consultant,” Santos says. “Being brought to the table with planners—that’s kind of where the nucleus of this whole thing is.”

ArtPlace is asking grantees to experiment with prioritizing process over product—in other words, to think like artists, who sometimes have no idea what the end product will be until they’ve gotten started. It’s an approach that can be messy, unpredictable, and risky—words that urban planners and developers don’t like to hear. “Each side has its own language,” Miller explains. “Trying to communicate can be a bit challenging.

“[For] artists, there’s fluidity and a lot of unknowns, and sometimes the unknowns are inspiring. For planners, it’s the opposite,” Santos agrees. “In that way there’s a lot of growth that happens there.” She’s inspired to see people within the organization who would hesitate to call themselves “creatives”—from those in LTSC’s Community Economic Development Department to the executive director himself—opening up to ways that art can be part of their practice.

Finding the right language is just as important externally as it is internally, especially in a community packed to the gills with working artists and arts organizations all scrambling to find funding. In such an environment, a community development organization receiving a $3 million arts grant might raise a few eyebrows. LTSC has been working to make clear that the grant’s goal is integrating the arts and artists into their existing work—and not re-inventing LTSC as an arts organization. “I think we’re still finessing our language with external partners who don’t know us as well, especially arts organizations and artists,” says De La Peza. “Part of this is understanding and recognizing how under-resourced and unacknowledged artists often are. They’re not at the table a lot of the time and not thought of as important stakeholders. We need to gain their trust.”

On the other hand, Santos observes, bringing creatives to the table early on not only affects the community development work, but it also encourages them to think more strategically about how their work can have a tangible, measurable impact on the community around them.

LTSC has developed an index it is using to assess how a particular project fits into the overall goals of the organization. It looks at what can be measured in that project’s process, final product, and audience; helps identify how a project addresses LTSC’s goals; and helps evaluate where different strategies are needed. Having a way to measure impact helps interpret between creatives and planners, and provides the balance between the planner’s need for quantitative strategy and the artist’s desire to, as Santos puts it, “think big.”

Shaping the Tree

With input from executive director Matsubayashi, the planning team landed upon a vision for “an equitable, sustainable, empowered Little Tokyo community of color with a vibrant culture.” This vision became the guiding principle for an interactive approach to cultural asset mapping that the team is calling +lab (“plus lab”).

A private Takachizu workshop with Sustainable Little Tokyo and +lab. PHoto courtesy of +lab

In partnership with Sustainable Little Tokyo, the +lab initiative launched in August 2016 in the soon-to-open Budokan of Los Angeles recreation center, one of LTSC’s latest developments, with an event called “Takachizu,” short for “treasure map” in Japanese. The idea behind Takachizu is to reflect the traditions, history, and creativity of Little Tokyo in an inventive way, and not just “sum it up in some book,” Santos says. “We wanted to create a temporary exhibit where we could gather all these assets, so people could share what they value about the place.”

In addition to kicking off +lab, the exhibit is a space where people can gather not only to learn about Little Tokyo, but to define it for themselves by contributing “treasures” of their own, which will be photographed and displayed with information cards. “What you’ll be seeing when you come in is a low-fi, incomplete exhibit in large print of various images of [cultural] assets” in Little Tokyo, says Santos.

Examples of such assets can be found on Sustainable Little Tokyo’s Takachizu blog: a piece of the original stairwell from the historic Nishi Honganji Buddhist Temple, an old shoebox from the legendary Asahi Shoes & Dry Goods store, even a crumpled receipt for a $5 bento lunch contributed by Little Tokyo resident Frank Lee. “I have grown a fond relationship with the bento lunches at Marukai Market,” wrote Lee on the information card accompanying the receipt. “It’s a very happy part of my day and important to my continued existence and fuel for me to work for a beautiful community/neighborhood.”

A particularly poignant moment at the inaugural +lab event involved Las Fotos, a local nonprofit housed in one of LTSC’s buildings that teaches photography to teenage girls. During Older Americans Appreciation Month, participants were given the task of taking portraits of senior members of the Little Tokyo community. The seniors were invited to come to the +lab to collect their portraits and to ensure that all ages, from youth to seniors, were brought into the event and encouraged to mingle. Bringing these groups together and putting them in dialogue through art is one approach to defining the “somewhat undefinable” character of Little Tokyo. It’s a bold way, as Miller says, of “trying to get people engaged not just so they can be informed but so they can be involved in the fight to really maintain this place they call home.”

But engaging a core constituency is not the only goal. “We hope for +lab to be a model for melding arts and culture into traditionally ‘non-creative’ work,” Miller explains. “It’s making creativity a normal part of the process, getting those who make the decisions to a mentality where they naturally initiate plans from a creative and experimental place.”

The fight for Little Tokyo’s soul is on the horizon. With the Little Tokyo/Arts District Station set to become the second busiest in L.A.’s light rail transit system, and luxury property developments cropping up in the area, the pressure is on to empower Little Tokyo to take an active role in determining its own future. Through the CDI initiative, ArtPlace has armed LTSC and Sustainable Little Tokyo with more tools to, as Fukushima says, “engage people in a new way and highlight Little Tokyo.”

How can Little Tokyo residents recognize the past and preserve the community’s legacy in the face of change? It starts with taking stock of the many different memories and narratives that shape the history of a single location. It starts with stopping to notice the person walking with her cane down the same street and across the same plaza every day, and honoring who that person is, how she got there, and what she remembers.

The Little Tokyo Service Center is one of six organizations selected to receive multiyear grants from ArtPlace America through the Community Development Investments (CDI) program. The program was geared to organizations that have not previously used arts and culture strategies in their community development work to help them integrate new tools and approaches and build new partnerships.

Want to learn about the other organizations that were selected for the CDI program? We’ve profiled two other grantees—the Cook Inlet Housing Authority in Anchorage, Alaska, and the Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership in Slayton, Minnesota.

Comments