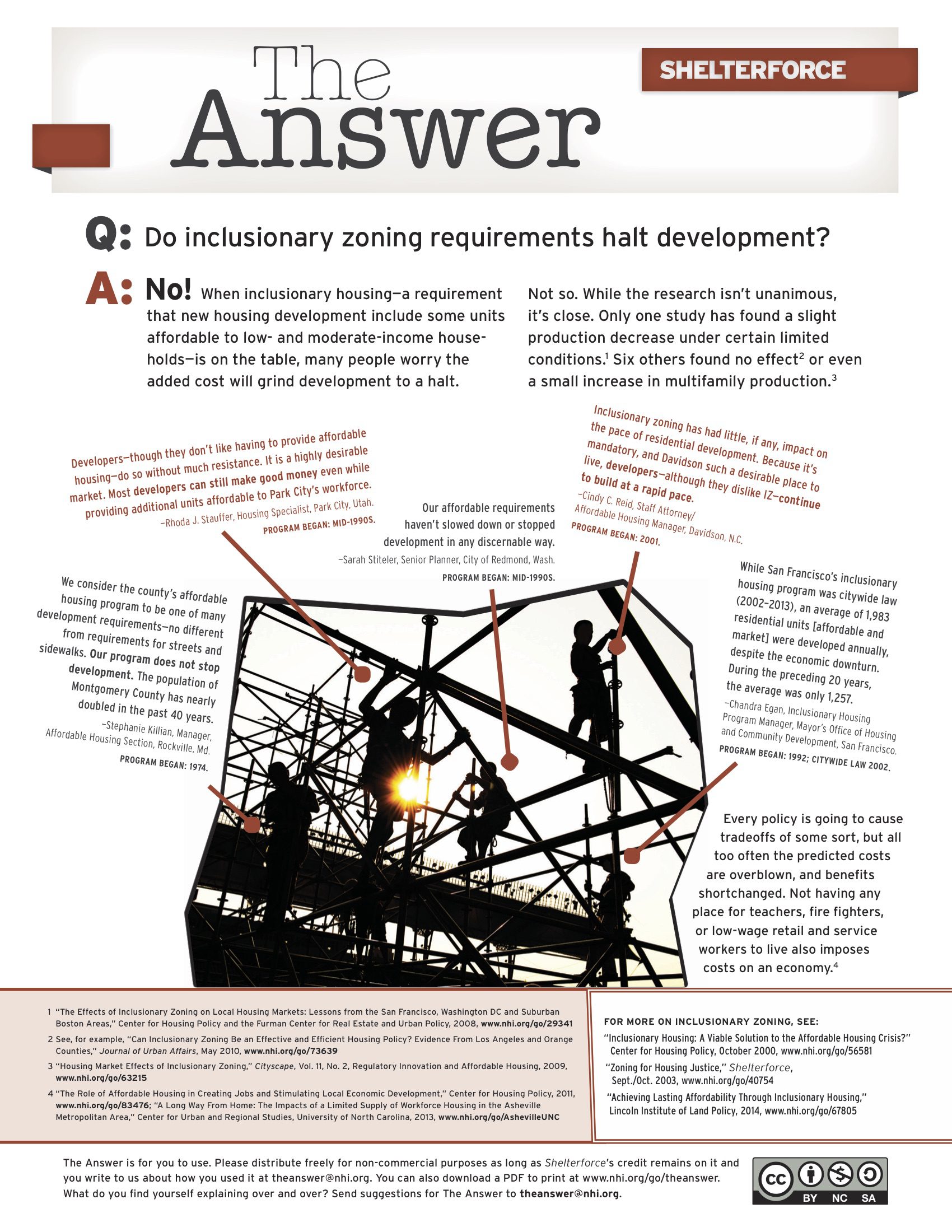

Photo courtesy of Bridging Communities

Over the past five years, multigenerational family households, defined as two or more generations of relatives (beyond parents and minor children) living together under one roof, have been steadily increasing in the United States. “A record 57 million Americans, or 18.1 percent of the population of the United States, lived in multigenerational family households in 2012, double the number who lived in such households in 1980,” according to a study published by the Pew Research Center in 2014.

Though the study suggested that the 2007 recession and young single adults living with their parents longer accounted for a large part of the increase, intentional incorporation of seniors into extended family households probably contributed as well. It’s common to hear of the struggling son or daughter working hard to provide for both children and aging parents who need care, but there are also independent older adults who are helping to support extended-family households and taking care of their grandchildren. When it comes to affordable senior housing, their needs are often overlooked.

For example, a few years ago the staff at Bridging Communities, a Detroit-based multi-sector grassroots collaboration focused on the needs of elders, noticed that many of its independent living facility residents were allowing their grandchildren to stay with them for extended periods of time. “They would come to visit, and never leave,” says Phyllis Edwards, executive director at Bridging Communities. This was problematic because the homes were specifically designed for, and only available to, seniors. The need for a new development was so great that Bridging Communities eventually decided to create housing specifically to accommodate seniors raising their grandchildren.

In 2008, Bridging Communities completed the first phase of Springwells Village, which consists of 24 affordable townhomes on three different sites throughout Southwest Detroit, specifically designed for “grandfamilies.” Unlike typical senior units, the homes have two or three bedrooms. They are located in a gated community that has a community center. Each home is ADA compliant, equipped with wide doors and wide floor plans for wheelchairs.

In its second phase, Springwells Village will add 48 single-family homes that are available to all family types, making the development an intergenerational housing community—one that explicitly includes multiple generations, though not necessarily under the same roof.

Generations, a development that is in the process of being built by the Native American Youth and Family Center (NAYA), in Portland, Oregon, is another good example of an intentionally intergenerational housing development. Generations is looking to specifically attract both elders and foster parents who seek to adopt or care for several foster children. “One in five Native American children in Multnomah County is in child welfare custody,” so this initiative is very important, says Shawn Fleek, NAYA program director.

Though many affordable housing developments make an effort to appeal to elderly adults by created age-segregated communities, NAYA doesn’t see the value in separating the elderly and the young. “We [Native Americans] are very family-oriented people; we seek advice from our elders, we eat meals together, and we really value their opinions,” says Fleek.

And in fact, the older adults who live at Generations will not just be receiving support, but are also expected to give. As NAYA’s website describes, “Community Elders become adopted grandparents and mentors who can ‘age in place’ with a renewed sense of purpose, helping with child care and providing wisdom. . . . A community like this can reduce poverty, improve health and wellness, and rebuild the cultural fabric of the Native community.”

Bridging Communities also sees the value in mixing generations within a development. “A lot of our grandparents are really outdated when it comes to homework,” says Edwards, “and they don’t really have the mobility to keep up with the activities the kids are involved with.” In the intergenerational setting, grandparents can independently take care of their grandchildren, and get help from younger parents when they need it. One of the seniors at Springwells, for example, babysits for a younger parent, who in exchange takes the senior to church and grocery shopping.

Some intergenerational communities, on the other hand, start with preservation and preventing displacement. In 2004, Habitat for Humanity of Greater Charlottesville purchased the 16-unit Sunrise Trailer Court in Charlottesville, Va. The development had been for sale, and its elderly residents at risk of displacement by incoming market-rate development. With the help of an AARP Foundation grant, Habitat instead purchased the park with the intention of turning it into a mixed-income community that would include subsidized rentals, affordable homeownership, and market-rate homeownership. The elderly residents were promised housing in the new development, says Dan Rosensweig, president of Habitat for Humanity of Greater Charlottesville. Habitat for Humanity also welcomed feedback from residents during the renovation process.

In the beginning planning stages of Sunrise Park, older residents mentioned that they found the two steps up to their older mobile homes to be burdensome. In response to that concern, Habitat for Humanity built a building with an elevator, zero-step entries, and units with a host of accessible features such as wider bathrooms, After learning that residents liked the basic configuration of their “trailers,” Habitat for Humanity also “tried to at least equal the square footage they had, and laid out the units to respect the ways they said they wanted to live,” says Rosensweig.

Rethinking the Household

When it comes to building housing for multigenerational families, there are three key needs that must be met: space, flexibility, and accessibility. Space and flexibility tend to go hand-in-hand; the larger a home is, the more flexibility it allows to accommodate larger than usual numbers of people. Larger homes also allow individuals to further tailor a home to their specific needs, such as adding an extra room for an aging parent, or building a ramp. Houses from the mid-20th century or earlier often have the only bathroom upstairs and the kitchen is downstairs, making it “kind of challenging” for someone older to navigate, says Kris Brogan, a board member at City of Lakes Community Land Trust. “If you have a larger home where you can make accommodations [it] makes it a little bit easier,” Brogan added. Multigenerational households combine their need for more space with all the accessibility concerns of senior households, from physical accessibility of the building to whether or not the location is accommodating to individuals who want to age in place.

According to a 2013 survey, described in the Urban Land Institute’s report on trends in multi- and intergenerational housing, “Multigenerational households show more of a preference than the total population for living in a community that is close to a mix of shops, restaurants, and offices (65 percent for multigenerational households compared with 53 percent of the total population); that has a mix of incomes (59 percent for multigenerational households compared with 52 percent of the total population); that enjoys public transportation options (60 percent for multigenerational households compared with 51 percent of the total population); and that has a mix of homes (57 percent for multigenerational households compared with 48 percent of the total population).”

Multigenerational households also look different in terms of how they pay for their housing—many have more than two income-earners, or have retired members contributing toward housing costs via Social Security or pensions.

Nonetheless, most lenders and government housing programs only consider the income of the head of household, or joint incomes between spouses, which can limit multigenerational families from purchasing the kinds of housing that best suits their needs.

For instance, let’s say there is a family composed of a married couple, an adult child and a retired aging parent. With their incomes combined they can afford a home that is large enough for all of them, but they can’t purchase it because the underwriting only includes the married couple’s income. Multigenerational families that find themselves in this position are often left to seek out housing individually, or risk settling for subpar living conditions together.

Jeremy Liu, principal of Creative Ecology and formerly executive director of the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation in Oakland, wrote for Shelterforce in 2011 that this type of practice “atomizes families” into nuclear units by not taking into account the way that modern families are living. Liu noted that multigenerational living can also take the form of families clustering in housing in the same neighborhood, or on the same block, even if they are not under the same roof, and said that policies should support those choices as well. “At federal, state, and local levels, we need housing policies that are family friendly and that celebrate and support the way we live,” Liu wrote.

Rethinking Design

Building for multigenerational families is not always easy. A few years ago, Staci Horwitz, the program director at City of Lakes Community Land Trust in North Minneapolis, noticed (and heard from residents) that there was a need for larger homes in North Minneapolis neighborhoods, especially ones that could support multigenerational families. Increasingly, “people were looking at duplexes to accommodate multiple generations in a single structure,” says Horwitz. Some expressed that they wanted their parents to live with them but needed “a little separation,” while others were immigrants seeking to accommodate extended families and also maintain some separation.

So she and her team proposed to create 1,600-sq.-ft. homes that included a single common area, three bedrooms, one and a half bathrooms, two kitchens, and locking internal doors separating them into two semi-separate living areas. These homes, essentially duplexes, would have allowed multigenerational families to live under the same roof, but control their level of interaction. This type of freedom was something that many residents expressed an interest in, especially individuals who had aging parents. “They wanted something that would allow them to be close to their aging parents, but also give them [the parents] the privacy and independence of having their own space,” says Horwitz.

Horwitz’s proposal was initially accepted by the Minneapolis City Council as is, but before she could move forward with it, it was determined that Minneapolis’s zoning laws did not allow accessory dwelling units, which is technically what she was proposing to create. Accessory dwelling units, often a good way to mix privacy with multigenerational living, can also help families overcome mortgage challenges such as those mentioned above, by casting some of the family members’ housing cost contribution as rent. Unfortunately, accessory dwelling units aren’t always permitted.

Horwitz had to revamp her entire idea. She was forced to remove the second kitchen, the locked door that would separate the home into two wings, and the half bathroom. In the end, she was left with 500-sq.- ft. single-family homes. Though she and her team were disappointed, they were fully aware of how ambitious the project was when they pitched it. “We understood that we were proposing something that didn’t fit 100 percent with the current zoning, but saw it as a need in the community,” she says.

Balancing location and space is not just a concern for lower income families. In 2013, The New York Times reported that four separate families purchased two luxury condos each at 10 Madison Square West in Manhattan with the intention of knocking down the connecting walls and creating multigenerational homes.

But for those who can’t afford one non-luxury condo, let alone two, clearly there is a need to adapt the kinds of housing available—and the policies that limit those options.

Comments